Last Thursday’s (January 4) in conversation book talk for IRISH EYES at the Barnes and Noble Upper West Side Manhattan was a magical evening (Subway train derailments aside). Fiona Davis was a superb moderator and the newly renovated bookstore is bright and airy and in every way conducive to chatting. But don’t take my word for it. Enjoy the video, and if you’d like a *signed* copy of IRISH EYES, you can pick one up at B&N at 2289 Broadway @82nd Street.

Tag: #HistoryMatters

The Windsor Hotel Fire of St. Patrick’s Day 1899

NYC’s Deadliest Hotel Fire Took 86 Lives

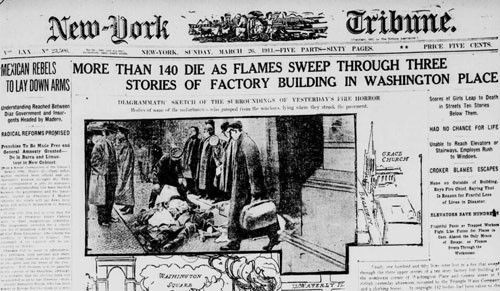

On March 17, 1899, the Windsor Hotel at 575 Fifth Avenue caught fire, the first smoke and flames billowing from the building just as the city’s annual St. Patrick’s Day parade reached 47th Street. Not even the proximity of the city’s firefighters marching by in their dress blues could save the grand hotel from burning to the ground. Nearly 90 people died, making the Windsor the deadliest hotel fire in New York and the worst commercial disaster until the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire of 1911.

Read the rest of the story on Medium.

Interview with Irish Central

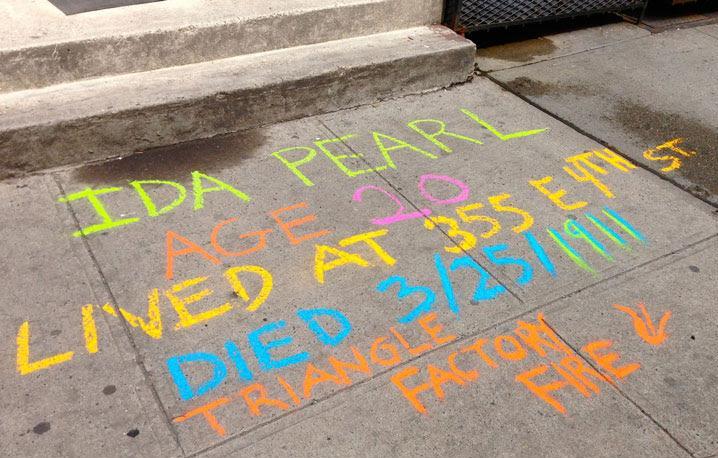

I recently sat down with Irish Central to talk about the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire of 1911, which marks its 110th anniversary this March 25th. Between research for my Gilded Age novel manuscript, Irish Eyes and my three-part podcast series with Irish historian Fin Dwyer, there was soooo much fascinating material that didn’t make it into either of those projects, leaving me lots to talk about, not only the grim facts of the fire but the workplace reforms won its wake.

The fire took the lives of 146 workers, most of them immigrant women and girls. The youngest victim was just 14 years old. Triangle policies such as denying workers fire drills and locking workroom doors from the outside greatly contributed to the catastrophic loss of life — the deadliest workplace disaster in New York State until 9/11.

In combing through the debris afterward, rescuers recovered fourteen engagement rings, a poignant reminder of the thwarted promise of so many young lives lost.

Check out my Irish Central interview here and then have a listen to the pod.

Tweet me your thoughts @hopetarr #historymatters.

Podcast – Episode Three, The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire of 1911: An Emigrant’s Experience

Episode Three, the final episode of my podcast series, “The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire: An Emigrant’s Experience” with Irish historian, author and podcaster, Fin Dwyer looks at the fire’s legacy through the eyes of two young women workers who survived it, Annie Doherty from County Donegal, Ireland, and Celia Walker from Przemsyl, Poland. One woman would disappear from the public record less than a decade later; the other would go on to achieve a modest version of the American Dream.

Meanwhile, the public outcry against the factory owners’ criminal negligence would fuel an unprecedented nationwide labor reform effort led by the International Ladies Garment Workers Union. For the first time in US labor history, women didn’t have to beg a seat at the bargaining table — they were leading the charge. 110 years later, we have these fiercely dedicated women to thank for fire drills and many other legally mandated workplace safety measures we take for granted today.

Catch up on the previous episodes here:

Episode One follows Annie’s and Celia’s harrowing transatlantic journeys to New York where both women would make their home, Annie in the notorious West side neighborhood of Hell’s Kitchen, Celia in the predominantly Eastern European Lower East Side.

Episode Two takes Annie and Celia from the citywide garment workers strike of 1909 known as The Uprising of 20,000 to Saturday, March 25, 1911 when the fire broke out on the factory’s eighth floor, trapping hundreds of young women and girls inside and killing 146, making it the most lethal workplace disaster in New York State until 9/11.

Have a listen and share your thoughts on Twitter where I post as @HopeTarr #HistoryMatters.

For Sharing on Social:

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire: An Emigrant’s Experience (Episode 3)

https://tinyurl.com/y3d9dtxy

#HistoryMatters #podcast

Don’t miss a thing! Sign up for my newsletter here.

Podcast – Episode Two, The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire of 1911: An Emigrant’s Experience

They called them the Shirtwaist Kings. Max Blanck and Isaac Harris, owners of the Triangle Shirtwaist Company, one of the largest ready-made clothing manufacturing firms in the United States and a principal provider of ladies’ button-up blouses, the go-to garment for the New Woman.

To the workers employed in their factories in Syracuse, Yonkers, Boston, Philadelphia and Manhattan, Blanck and Harris were more than kings. They were as good as gods, wielding the power of life and death over hundreds of employees, mostly immigrant women and girls like Annie Doherty from Ireland and Celia Walker from Poland, the subjects of my new three-part podcast series on the fire, a collaboration with Fin Dwyer, Irish historian, author and creator of the acclaimed Irish History Podcast.

Episode One follows Annie’s and Celia’s harrowing transatlantic journeys to New York where both women would make their home, Annie in the notorious West side neighborhood of Hell’s Kitchen, Celia in the predominantly Eastern European Lower East Side.

Episode Two, which launched 1/18/21, follows Annie and Celia from the citywide garment workers strike of 1909 to that fatal Saturday, March 25, 1911 when the fire broke out on the factory’s eighth floor. Within 30-minutes, 146 workers would be dead, another 78 injured, victims of what would be the deadliest industrial disaster in New York State until the 9/11 terrorist attack.

Episode Three, which looks at the legacy of the fire in the lives of survivors and in the larger landscape of labor reform, will post Monday, January 25.

Have a listen and then share your thoughts on Twitter where I post as @HopeTarr #HistoryMatters.

For Sharing on Social:

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire: An Emigrant’s Experience (Episode 2)

https://tinyurl.com/yxhn6a66

#HistoryMatters #podcast

Don’t miss a thing! Sign up for my newsletter here.

Podcast – The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire of 1911: An Emigrant’s Experience

I’m thrilled to announce the launch of “The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire of 1911: An Emigrant’s Experience,” a three-part podcast with Irish historian, author and podcaster Fin Dwyer. I first met Fin in 2018 at an event at the American Irish Historical Society in Manhattan where he was the guest speaker, thought he was brilliant and approached him afterward about how we might collaborate to put together a podcast program for the fire’s 110th anniversary on March 25, 2021. Nearly three years later, and more than 3,000 miles and five hours apart — Fin in Kilkenny and me in NYC — here we are!

The fire at the Triangle factory, housed in the Asch Building (today the Brown Building, part of New York University) took the lives of 146 workers, most of them immigrant women and girls, and injured 78 others, making it the deadliest workplace disaster in New York State until the terrorist attacks of 9/11. Each approximately 30-minute podcast episode looks at a different aspect of the fire as seen through the eyes of two immigrant factory workers who lived it: Annie Doherty, an Irish Catholic from Finn Valley in Ireland’s County Donegal and Celia Walker, an Eastern European Jew from Przemysl in southwestern Poland, in the late 19th century part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Listen to Episode One here, which follows Annie’s and Celia’s harrowing transatlantic journeys to turn-of-the-century New York where both women would make their home, Annie in the notorious West side neighborhood of Hell’s Kitchen, Celia in the predominantly Eastern European Lower East Side.

Episode Two: Fire and Episode Three: Legacy will post Monday, January 18 and Monday, January 25, respectively. Have a listen and then share your thoughts on Twitter where I post as @HopeTarr #HistoryMatters.

For Sharing on Social:

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire: An Emigrant’s Experience

https://tinyurl.com/y38ntjuk

#HistoryMatters #podcast

Don’t miss a thing! Sign up for my newsletter here.

Happy Birthday, 19th Amendment!

This August 18th marked the centennial of ratification of the 19th Amendment to the Constitution “granting” women the right to vote. The quotes are intentional. Women weren’t granted the ballot – we TOOK it, after 70+ years of strife, sacrifice and single-minded dedication, all while maintaining marriages, raising children–and sometimes falling in love.

To put a human face on this epic struggle, I’ve written about the little known love story of two powerhouse suffragist leaders: “Carrie Chapman Catt and Mary Garrett Hay, The Boston Marriage that Won the Vote for U.S. Women.” Read the article for FREE on Medium by clicking on this link. Below is a taste:

When president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, Carrie Chapman Catt (1859–1947) first clapped eyes on Mary “Mollie” Garrett Hay (1857–1928), president of the New York Equal Suffrage League, in 1895, Carrie was five years’ married to her second husband, George Catt. Soon after George’s death in 1905, Carrie would make her home with Mollie. The women would share a common cause and a roof for the next thirty years. As fellow activist Maud Wood Park remarked, “Mrs. Catt was essentially a statesman; Miss Hay, a politician, and together they were, in most cases, invincible.”[i]

A Dream Team

Carrie and Mollie first met in 1895 while attending the NAWSA convention on January 31 to February 5 in Atlanta.[ii] It seems to have been lust at first sight, their courtship the very opposite of a slow burn. That summer, while Carrie’s civil engineer husband, George was away on business, Mollie moved in with Carrie at the Catt apartment[iii] at Osborne Apartment House, №26 West 57th Street. As noted by Mary Peck, Carrie’s official biographer, that summer was the beginning of the “intimate collaboration which united them for many years.”[iv]

George’s return spelled the end of Carrie’s and Mollie’s idyll.[v] What he thought of his wife’s suffrage partner and new bestie remains unclear. Perhaps tellingly, in January 1896, he took time off work to accompany Carrie to the annual NAWSA convention in Washington, DC, where he addressed the assembly on “Utah’s Victory the Result of Organization; Its Lesson.” In calling George to the podium, President Susan B. Anthony said, “It gives me pleasure to introduce Mr. Carrie Chapman Catt… I mean, Mr. George W. Catt.”[vi]

If George’s attendance was an attempt to win back his wife, it was not to be. Throughout the late 1890s, Mollie and Carrie continued to work and travel together, with Mollie acknowledged within the movement as Carrie’s special friend and companion. In 1899, the women visited twenty states, attended fifteen conventions and made fifty-one speeches, a grueling tour de force that covered thirteen thousand miles.[vii]

Undoubtedly, Carrie was the shiny penny of the pair, fawned over by both male and female reporters, one of whom described her as “…a tall, handsome woman with brown hair and blue gray eyes and a gentle yet strong face.”[viii] A gifted orator, she projected her magnetism into a crowded lecture hall with the same easy grace she brought to an intimate at-home in her own parlor.

But Mollie was no shrinking violet. A crack fundraiser and dealmaker, Mollie possessed enormous powers of persuasion, a steady determination we today might call “soft power.” Decatur Herald reporter Lillian Gray extolled Mollie’s calm, easy nature and winning ways.

“Others may lose their heads or tempers or fly off on a wild goose chase; she never does. She is a woman with prematurely white hair like a glory round her head, with sparkling dark eyes, flashing white teeth and a merry smile. You will not find a brighter, handsomer, more wholesome woman in a journey across this continent, that journey Mary Garrett Hay herself has taken so many times in the interest of her sex. She has a strong, sincere, energetic voice, the voice of a woman who can make things hum.”[xi]

Not everyone was a fan…

Read the rest on Medium – you do NOT have to be a subscriber to do so. And please be sure to leave a “Clap” before you go.

Onward/upward,

Hope

Get TEMPTING for FREE thru 3/19/20

Get the TEMPTING Ebook FREE

The pleasure of a good book has seen me through the toughest of times – and these certainly qualify. Which is why I’m offering TEMPTING as a FREE ebook on Kindle through Thursday, March 19 (offer ends midnight). Download the book and discover why RT BOOKReviews selected it as “Best Unusual Historical.” If you enjoy Christine and Simon’s unique love story, please take two ticks to pay it forward – leave a short review.

Be well,

Hope

Stinky Boots – Hygiene and Hot Sex in Historical Fiction

Getting Down and Dirty in Historical Fiction

Chamber pots, head lice, the pox—and I don’t mean the kind prefaced by “chicken”—writing historical fiction, especially romantic historical fiction, calls for striking a balance between authenticity and contemporary sensibilities. I still recall, with lingering discomfort, watching Braveheart for the first time. Spending nearly three hours with Mel Gibson’s William Wallace and his men blanketed in sweat, blood, and woad was nearly as excruciating for me as the final execution scene.

In PBS’s Sanditon, adapted from Jane Austen’s unfinished novel set in an upstart coastal resort striving to be the next Brighton, Sidney Parker (Theo James) opts for a refreshing — and unencumbered — solo sea bath, emerging from the cleansing froth just as Charlotte Heywood (Rose Williams) trots up. The birthday suit booty comes early on in episode two, which surely would send Miss Austen clutching her pearls. Or, more properly, turning in her tomb.

Getting Wet

In Medieval times, providing a bath was part and parcel of the hospitality on offer to visiting knights and other honored male guests. The ritual was performed in private and hands-on by the chatelaine of the castle—talk about your potentially sexy novel scenario!

England’s Queen Elizabeth I couldn’t abide malodors from her courtiers or herself. Her commitment to cleanliness called for hauling her private bath on every stop of every Royal Progress.

But what about everyone else, those whose social station fell somewhere between lordly and lowly?

Making an indoor bath happen was a time-consuming labor. Water was brought in from an outside well, heated in the kitchen, and then carried in heavy, copper-lined buckets up flights of often steep, winding stairs. But there were alternatives. The remains of hot rocks baths, communal bathing pools lined with smooth stone and sometimes roofed against inclement weather, have been excavated throughout Scotland and parts of Ireland. Some sites were proximate to naturally occurring thermal springs, but others were not. In the latter case, buckets of heated stones or rocks were periodically added to the water, maintaining a semi-constant warmish temperature. Quelle steamy story setup for an historical romance writer!

Regency rake and original male fashionista, Beau Brummell is known as much for bringing fastidiousness into vogue as he is for his elaborate snowy waterfall neck cloth and champagne-based boot blacking. We have Brummell to thank for bringing regular bathing to the in crowd.

Toothsome Tales

Medieval people also took regular care of their teeth, and I don’t only mean visiting the blacksmith or other local tooth puller once things got… ugly. Tooth powders were the precursors to Crest and Colgate. Certain wood barks were ideal for cleaning between teeth. Chewing fennel and other breath-freshening seeds was a common practice between and after meals—early Altoids! Recipes for soaps and bath salts were passed down from mother to daughter.

Getting Physical

By the late 1990’s and early aughts, historical romances began embracing grittier, less airbrushed depictions of hygiene and intimacy. Take, for example, Outlander by Diana Gabaldon, the launch to her brilliant and beloved Scottish time travel series. During Jamie and Claire’s wedding night lovemaking, his curious kisses stray… south. The usually randy Claire halts him, protesting that he must be put off by her unwashed state. Smiling, Jamie likens the situation to a horse learning his mare’s scent. And proceeds to prove how very not put off he is.

We don’t call them “heroes” for nothing. 😉

By now most of us are familiar with the infamous tampon scene in Fifty Shades of Grey by E.L. James. In historical romances, our heroines rarely have their periods until they don’t and then only in the service of the story, notably advancing the tried-and-true “marriage of convenience” trope. Rarely do we see in fiction what dealing with menstruation must have meant for our foremothers. Plug-like devices for blocking flow are traceable to ancient Egypt (papyrus) and Rome (wool). The modern, mass-produced tampon wasn’t invented until 1929. Patented in 1931 by creator Dr. Earle Haas, this remarkably liberating new product was later trademarked “Tampax.”

Such advances are all well and good but what about having the personal space to put them into practice? Not even gentlewoman Jane Austen had a room of her own. In Irish Eyes, my women’s historical fiction debut (on submission), my Irish immigrant heroine shares a three-room Lower East Side, New York tenement flat with a family of seven. Finding the privacy to change clothes, bathe, relieve herself and manage menstruation as she must is a challenge few of us can imagine facing. Yet as documented by turn-of-the-century reformer, Jacob Riis in How The Other Half Lives, those were the very circumstances in which the vast majority of immigrant arrivals to New York found themselves.

Historical fiction fans are an exceptionally savvy lot. Anachronisms invariably jar us from the story; too many may well have us pulling the plug without reaching the end. And yet none of us truly knows what it was to live in a previous century or, for that matter, generation. We conduct our research in the service of the story. Fortunately, romantic historical fiction focuses not on the ordinary but on the extraordinary. Not on tepid tenderness but on grand passion and great stakes. Not on how dark, dreary and dirty life can be but on how amazing real love is and always will be.

An earlier version of this article appeared in Heroes & Heartbreakers.

Copyright Hope C. Tarr

Read the first chapter of Tempting, my award-winning Victorian-set historical here, then get the book on Amazon and elsewhere for #99cents.

Twitter @hopetarr Instagram @hopectarr

The London Foundling Hospital

I recently ran across Orphans of Empire by Helen Berry, a new nonfiction book chronicling the history of the London Foundling Hospital, Britain’s first home for abandoned children, a find that thrilled me to no end because a) lifeline Anglophile b) lifelong history geek and c) the LFH is the principal setting for my late Regency romance, Claimed By the Rogue.

The LFH was founded by sea captain Thomas Coram, a childless widower with a hefty purse and the heart to match it. Appalled by the 1,000 children abandoned to the London streets each year, Captain Coram resolved to put his money where his morals were. In 1735 he petitioned Britain’s King George II to establish a “hospital” (a philanthropic institution dispensing hospitality) for the education and maintenance of foundlings. Twenty-one aristocratic ladies signed on to Coram’s petition, which quickly picked up steam as a fashionable philanthropy. Coram received his Royal Charter in 1739; the first children were admitted in 1741. Prominent patrons included the painter, William Hogarth and composer George Frideric Handel; the latter served as the hospital’s first governor.

The LFH no longer exists – the gracious Georgian brickwork building in Bloomsbury was demolished in 1926 and the institution ended in the 1950s – but its 200+ year history is preserved in the Foundling Museum in Brunswick Square. Perhaps the most feeling artifacts on exhibit are also the humblest: the museum’s collection of Foundling Tokens – buttons, jewelry, coins etc. – left behind by the mothers, a last tangible link to the child they hoped one day to reclaim. Sadly, such hoped for reunions were rare; the vast majority of tokens remain with the museum.

If an orphanage sounds like an unconventional setting for a Regency romance, you would be right! In Claimed By The Rogue, my heroine, Lady Phoebe Tremont, volunteers at the LFH after her fiance, Captain Robert Bellamy, is presumed lost at sea. Six years later, Robert returns to find a very different Phoebe than the sweet, pampered miss he left behind. Fiercely devoted to the foundlings under her care, determined to continue in her duties despite her impending marriage to an expat French aristocrat, Phoebe is very much a woman ahead of her time. To win her back, Robert makes an offer not even Phoebe can refuse. He’ll donate 100 pounds a day to the institution she lives and breathes provided Phoebe allows him to shadow her in her daily duties.

Spoiler Alert! He falls head over feet for the new impassioned, socially-minded Phoebe – it IS a romance – as well as the adorable orphans under her care.

Enjoy this short excerpt from Claimed By The Rogue and join me on Twitter @hopetarr and Instagram @hopectarr where I post fun historical tidbits at #HistoryMatters.

“Don’t you ever rest?” Robert asked, trailing Phoebe down yet another labyrinthine passageway. So far they’d visited the governors’ court room, chapel, girls’ dormitory, boys’ dormitory, sundry classrooms, and even the morgue, all of it at a brisk to breakneck pace.

She glanced back at him over her shoulder. “I haven’t the need, but don’t let me hinder you from doing so.”

“No, I’m fine. I was only concerned for you.”

“Hmm,” was all she said before darting down yet another white-walled corridor.

Lengthening his stride, he found himself wondering how it was that such a graceful woman managed to move so swiftly. The indolent maid of his memory seemed to have acquired the gait of a racehorse, not that he considered complaining of it. Admiring the hind view of those slender, swaying hips made for a deucedly pleasant pastime even if the reek of turpentine and lemon oil was beginning to block his nose.

The ended their tour at the infirmary. The strong smell of vinegar permeated the vicinity. A glass-front apothecary cabinet containing myriad meticulously labeled clear jars, a washing bench outfitted with a bandage roller and stacked bedpans and a leather bound ledger presumably for recording the circumstances of patients comprised the long, narrow room. Phoebe’s hushed conference with the attending nurse secured their admission. Robert followed her along the queue of narrow cots, all but one of them unoccupied.

“Feeling a bit better today, Sally?” Phoebe asked, pausing to rest her hand upon the child’s brow, her swollen jaw banded by a camphorous cloth.

The girl, Sally, shook her head, wincing. “Tooth hurts terrible.”

Phoebe stroked a hank of brown hair back from the girl’s forehead. “I’m sure it does, poppet, but at least your fever’s down. Once the foulness finishes draining, you’ll be right as rain.”

Dull eyes looked up into hers. “Yes, miss.”

Most in Phoebe’s position would have moved along but instead she lingered. “I was going to give this to you later but now shall serve.” She reached into her gown’s pocket and pulled out a cloth-covered doll.

The fevered little face lit. “Oh, miss, thank you!”

Phoebe tucked the doll into the crook of Sally’s arm and straightened. “Not only a doll but a magic doll. Whenever your tooth troubles you, squeeze upon her and she’ll help keep the pain away.”

Looking on, Robert felt a powerful pull in the vicinity of his heart. Phoebe had the makings of a marvelous mother. The earlier scene in the classroom and now this strengthened his resolve to do all in his power to ensure that her future children would be his, not Bouchart’s.

Seeing her about to turn back to him, he quickly made a mask of his face. “You needn’t fear infection,” she said archly, misreading him yet again. “Mostly we treat minor injuries, sprained ankles and, in Sally’s case, toothache. More serious cases are transported to St. George’s.”

“My constitution is that of an ox,” he answered, no idle boast. Given the fevers and pestilence to which he’d been exposed, an abscessed tooth and a few running noses hardly seemed of note. Stepping away from the beds with Phoebe, he asked, “How did you come to volunteer here?”

She hesitated. “In an odd way, I have you to thank for it.”

“I?” Even strongly suspecting he would regret it, he had to ask, “How so?”

“After we were told you were…lost, I wasn’t entirely certain what to do with myself, how to go on. Coming here began as a crutch, a reason to rise from bed each morning. Over time I began adding days, heartened that it was in my power to do some good.”

His kitchen conversation with Chelsea came back to him. She draped herself in black crepe and bombazine for a full year as though she were your widow in truth. There were times we feared she might take her own life.

“How does your mother feel about your laboring?”

She lanced him a look. “You mean my eccentricity, or so Mother calls it. She’s pinning her hopes on marriage proving the cure. To be fair, I should admit that she is hardly alone in her censure. Barring Chelsea and Anthony, most members of the ton think I’m daft to spend my days fraternizing with orphaned children, whom they’re convinced will amount to nothing more than cutpurses and prostitutes.

Watching her closely, he ventured, “And Bouchart, what does he say?”

She hesitated, the pause telling or so it seemed to Robert. “Aristide tolerates my employment for the present though he too assumes I’ll give it up of my own accord once we’re wed.” She paused, her quicksilver gaze honing onto his. “He’s mistaken.”

“I admire you for following your passion.”

She looked at him askance.

A renegade curl clung to the side of her cheek, which was neither pale nor waxen as it had been after her faint but a healthy, becoming pink. Resisting the urge to reach out and brush it back, he shook his head. “No really I do.”

Admire her though he did, he was in no way inured to how enticing she not only looked but smelled—vanilla from the milled soap she’d always favored, lavender from the eau de cologne she preferred to perfume, and some spicy citrus scent he didn’t recall from before but badly wanted to sample.

A baby’s balling drew their attention outside. Robert joined her at the window overlooking the front lawn. Fifty-odd women and children, the latter of various ages from infancy to adolescence, stood in queue extending from the arcaded entrance gate to the circular drive. The group had grown considerably since Robert had arrived. Passing them by, he’d seen more than one cheek tracked with tears but aside from the occasional wailing infant, they’d waited in stoic silence. It seemed they waited still.

“Good God, there are so many of them.”

Letting the curtain drop, Phoebe sighed. “I know. Every Monday brings the same sad sight. I’d thought by now to be accustomed to it, but after five years it still breaks my heart.”

“Have the London parish houses grown so lax in dispensing relief?

Her arch look told him he’d said the wrong thing—again. “They’ve not come for alms but to surrender their children. Only babes of twelve months or younger are accepted, and the mother must stipulate that the child is the fruit of her first fall—born out of wedlock. Admission is by ballot. Every Monday, a man is sent out with a leather bag of colored marbles. Each woman is entitled to draw only one from the bag. White entitles her child to admission subject to passing the medical examination, red to be put on a waiting list in case one of the accepted children is found to suffer from a malady of an infectious nature, and black—”

“Mother and child are turned away?”

Eyes suspiciously bright, she nodded. “It sounds heartless, I know, and in a way it is, but we haven’t beds for them all. Truth be told, we haven’t room for the ones we do take in. Presently we’re at four hundred and ten and that’s with several of the younger boys and girls sleeping two to a cot.”

He’d thought himself hardened to sad, suffering sights, but apparently he wasn’t as toughened as he’d supposed. “What will happen to them?”

“Once they pass the medical examination, they’re sent to the country for fostering. At four or five years of age, they’re brought back here, the boys to learn a trade, the girls to train for domestic employment. When the boys reach fourteen, the governors arrange indentures for them; many end up enlisting in the army. Settling the girls is more difficult, but every effort is made to find them suitable situations.”

Like a surgeon probing a wound, he had to know. “And what of those who are turned away?”

She shrugged but once again her eyes, silver blue irises awash in unshed tears, confirmed how very deeply she cared. “Some will be abandoned. Others will starve alongside their mothers. Still others still will seek refuge in the workhouses or…worse.” A pained look crossed her face. “Last winter a newborn was discovered in a…rubbish bin behind the hospital kitchen. He’d been dead some hours, of exposure or so the resident physician judged.” She turned her face away.

He braced a hand upon the sill, bringing their bodies ever so slightly brushing. “Surely something more may be done? What of the fathers? Haven’t they any say in whether or not their children are given up?”

She turned back to glare at him, her quicksilver gaze once more sharp as Damascus steel. “Do you honestly believe that even one of those women standing out there would give up her child if she might choose another course, if she herself hadn’t been abandoned?”

Abandoned—so there it was, the crux of Phoebe’s philanthropic passion. Clearly she felt an affinity with these women who’d been abandoned by their men to fend for their offspring and themselves.

“I only meant that it seems a father should have some rights, some say at the very least. Conceiving a child requires both parties, after all.” Gaze on hers, he owned how very much he wanted to make love with her and babies with her, the yearning to plant his seed inside her so fiercely primal he felt a sudden aching in his loins.

“One of the prerequisites for participating in the balloting is that the father must have deserted both mother and child. Deserted, Robert. I’d think you of all people would understand that.”

He swallowed against the pain pushing a path up his throat. “I didn’t desert you.”

She answered with a sharp laugh. “You chose to stay away and leave me to think you dead. If that’s not desertion, what is?”

“I chose to return when I knew I might be a fit husband for you in every way.”

After the torturers had gotten through with him, it had taken him months before he’d been able to stand the sight of himself in a mirror; closer to two years before he could bear so much as a hand upon his shoulder without flinching. How could he have come to her then, broken, a wreck? Better to allow her to think him dead and remember him as he’d been then to foist the leavings of himself upon her, a shell empty of all but pain and horror. Returning ere now would have been the ultimate selfishness or so he’d told himself. But staring into Phoebe’s face, he was no longer so supremely certain. The woman before him was fashioned of sturdier stuff than the girl he’d left behind. That girl would have crumpled at the sight of him but the strong, poised woman he saw before him might have proven equal to the task.

Her gaze narrowed. “And now you are too late, for I have a husband or at least I shall before the month is out.”

Before the month is out! Robert felt as though an invisible fist plowed him in the solar plexus. In the past, controlling his reaction to the pain, pretending to no longer feel or care, had served as his best defense, his strongest weapon.

Calling upon that hard-learned stoicism now, he summoned a smile. “What a coincidence, for I too will be embarking upon my next voyage at the month’s end but not before I have the pleasure of seeing you as a bride, I hope.”

Phoebe’s smile slipped.

“For now, I am afraid I must away. I have another appointment to attend.”

“Pray do not let me keep you from your pressing business,” she retorted, sounding much like her mother. Judging from her planted stance, he gathered she didn’t mean to walk him out. Just as well, he supposed for he needed some time to recover from the blow she’d just dealt him.

Heading for the door, he turned back. “What ungodly hour shall I arrive tomorrow?”

She shrugged. “Anytime or not at all, as you wish.”

“If you treat all your benefactors in such a shrewish fashion, ‘tis a mercy you have a roof and four walls,” he answered, a deliberate reminder that he was, in point, paying for her company if not her goodwill.

Releasing a sigh, she capitulated, “Oh, very well, nine o’ clock sharp and mind if you’re late, I shall bar the classroom door and you may wait out in the hallway until the session finishes.”

“My dearest Phoebe, I wouldn’t dream of being late.”

Stepping out into the hallway, Robert considered that six years was quite late enough. He didn’t mean to waste so much as a single second more.

Copyright: Hope Tarr

To read the rest of Lady Phoebe and Robert’s second chance at love story, buy the ebook at any of these online retailers.